The Narrative Shield: Why Your “Hyper-Growth” Might Be a Lie

A forensic analysis of narrative fragility in B2B SaaS.

I’m going to start with a statement that might make you uncomfortable.

If you are a B2B SaaS founder or Product Marketing Manager (PMM) seeing “up and to the right” charts, you might not be succeeding.

You might just be shielded.

We’re programmed to believe that revenue growth is the ultimate validation. If customers are buying, we must have Product-Market Fit (PMF), right? If ARR is doubling, our story must be resonating, right?

Not necessarily.

What if those “up and to the right charts” were benefitting from a specific market vacuum—a temporary lack of competition in a high-demand niche? Customers weren’t buying because they resonated or loved the vision; they were buying because they had no other choice.

Startups often confuse this for Product-Market Fit (PMF).

In reality, they have a shield.

And shields, by definition, are temporary.

I’ve spent the last few months obsessing over this.

So I conducted a forensic analysis of companies that looked unstoppable right up until the moment they evaporated—companies like HipChat, InVision, Hopin, and BlueJeans.

My analysis reveals a dangerous phenomenon governing the rise and catastrophic fall of a specific subset of unicorn-status B2B SaaS companies.

I call this phenomenon the “Narrative Shield.”

Here is the definition I’ve crystallized:

“The Narrative Shield is a temporary protective covering—composed of favorable macroeconomic conditions, lack of incumbent competition, or specific crisis-driven demand—that obscures critical deficiencies in a company’s product storytelling and core value proposition.”

When a startup enjoys a strong Narrative Shield, its growth metrics (Customer Acquisition Cost, Annual Recurring Revenue, Net Dollar Retention) often present false positives. The market assumes these metrics are the result of Product-Market Fit (PMF) and a resonant product story.

But they aren’t.

In this deep dive, I’m going to walk you through an exhaustive examination of the Narrative Shield. We are going to dissect the specific narrative failures of fallen giants to understand how they left themselves exposed to competitors who wielded superior storytelling architectures.

If you are a SaaS founder or PMM, buckle up for this is your diagnostic tool. This is how you find out if you are building a long-term growth engine, or just riding a tailwind.

Inside this Deep Dive:

Narrative Shield’s Theoretical Framework

Case Study 1: HipChat vs. Slack

Narrative Failure: “Communication” vs. “Collaboration”

Migration Friction: A Failure of “Sticky” Narrative

Atlassian Stride Pivot: Too Little, Too Late

The Capitulation: Narrative Surrender

Insights and Ripple Effects

Case Study 2: InVision vs. Figma

The Vaporware Crisis: InVision Studio

Figma and the “Multiplayer” Narrative

The Collapse: From $2 Billion to Zero

Third-Order Insights: The End of the File-Based Era

Case Study 3: Hopin’s Crisis Narrative Shield

False “Future of Events” Manifesto

The Shield Dissolves: The Return to Physical

The Valuation Collapse

Hopin’s “Virtual Venue” Trap

Case Study 4: BlueJeans vs. Zoom

Zoom’s Viral Simplicity

The “Video Quality” Myth

The Sunset

The Calculus of Narrative Erosion

Diagnostic Indicators of a Narrative Shield

The Fix: Paying Down “Story Debt”

Conclusion: Don’t Mistake a Tailwind for an Engine

Words count ~4,400 | Estimated read time 15 mins.

Hi I’m Victor Eduoh, and welcome to Product-Led Storytelling, my weekly deep dive newsletter on product storytelling, becoming a better SaaS product storyteller, and excelling as a product marketing manager (PMM).

Narrative Shield’s Theoretical Framework

Before we inspect the wreckage, let’s agree on the physics of the crash.

We’re trained to believe that revenue is truth. If people are paying, we must be doing something right.

But my analysis suggests that in shielded companies, revenue growth is a lagging indicator of environmental friction.

When the environment offers high friction for the buyer—for example, a sudden global pandemic forcing remote work, or a total lack of design collaboration software in a browser-based world—buyers will adopt tools that have weak narratives simply because they offer functional utility.

I call this the “Utility Trap.”

The Narrative Shield, therefore, creates a false sense of security for the founding team. This shielding effect is particularly insidious because it distorts the feedback loops essential for startup survival. When revenue flows easily due to a shield, leadership often interprets this as validation of their product vision. They double down on features and engineering, neglecting the “soft” work of narrative construction. You attribute your success to your “genius” product positioning, when in reality, it’s just the external tailwinds.

You assume the customer is buying the drill because they love your brand of drill. In reality, the customer is frantically buying the drill only because there is no one else selling a way to make a hole. The moment a competitor appears who sells “a perfectly crafted living room wall” (the outcome, not the tool), the customer defects. Why?

Because they never cared about the drill in the first place.

This distinction is the difference between Product-Market Fit (PMF) and Narrative-Market Fit (NMF).

PMF asks: Does the product solve the immediate pain point? (e.g., “I need to send a message to my colleague.”).

NMF asks: Does the product’s story align with the user’s aspirational identity and the long-term strategic goals of the buyer’s organization? (e.g., “I want my organization to be agile, transparent, and connected.”).

The companies we’re about to analyze largely achieved PMF. They engineered functional utilities. But they failed significantly at NMF. They failed to engineer meaning.

And when a competitor entered the market with both PMF and NMF, the incumbent’s Narrative Shield collapsed, revealing a fragile customer base with no emotional loyalty to the brand.

Let’s look at the first example.

Case Study 1: HipChat vs. Slack

If you were a developer in 2012, you probably used HipChat.

Before 2013, Atlassian’s HipChat was the dominant force in developer-centric chat. Acquired by Atlassian in 2012, HipChat possessed a robust Narrative Shield formed by the lack of viable alternatives and its deep integration into the Atlassian ecosystem (Jira, Confluence).

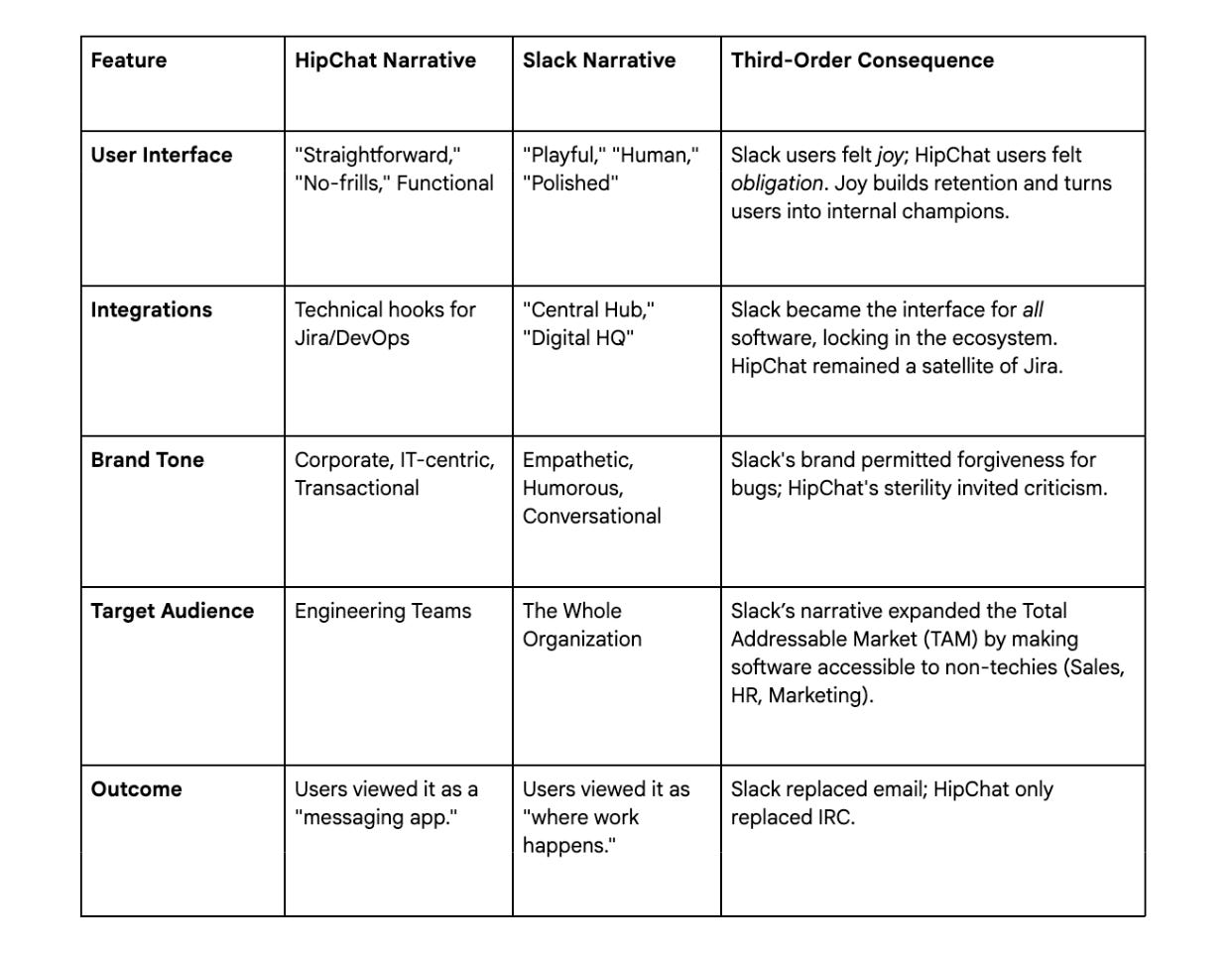

HipChat’s narrative was strictly utilitarian: “Group chat for teams.” It focused on the mechanism of communication rather than the quality or experience of that communication.

Atlassian’s strategy was logical but emotionally hollow: bundle chat with the project management tools developers were already using. This created a “moat of convenience.” HipChat offered a straightforward design, prioritizing “ease of navigation and clarity” over “visual flair”. For a time, this was enough. The “no-frills” approach appealed to a specific demographic of systems administrators and backend engineers who viewed software as a utility to be tolerated rather than enjoyed.

However, this utilitarian narrative—”It works, and it connects to Jira”—masked a growing dissatisfaction. Users described the interface as functional but uninspiring. The “straightforward” design was actually a euphemism for “sterile.” While HipChat provided essential integrations, it failed to capture the imagination of the broader workforce. It was a tool for the basement of the organization, not the boardroom or the creative studio.

Narrative Failure: “Communication” vs. “Collaboration”

HipChat’s fundamental narrative error was framing its product as a utility—a pipe through which text flowed. Utilities are commodities; they are replaced the moment a cheaper or slightly more reliable pipe appears.

Slack, launching in 2013/2014, did not compete on utility. It competed on empathy and organizational transformation. Stewart Butterfield, Slack’s CEO, explicitly embedded “empathy” into the company’s core values, a stark contrast to the purely functional ethos of HipChat. Slack’s tagline, “Where Work Happens,” was a narrative coup. It reframed the chat window from a place to type messages (HipChat’s story) to a digital headquarters—an operating system for the modern enterprise.

This narrative shift was supported by profound product design choices. Slack was “visually appealing” with “customizable themes” and “emoji reactions”. These features were not frivolous; they were narrative devices. They signaled that humans were using the software, not just resources. By allowing users to personalize their environment, Slack created a sense of ownership that HipChat’s “restrained” customization never achieved.

Table 1: Comparative Narrative Architectures (HipChat vs. Slack):

Migration Friction: A Failure of “Sticky” Narrative

A critical piece of evidence regarding the strength of Slack’s narrative comes from teams that attempted to switch back to HipChat. Some organizations, lured by the lower price or deep Jira integration of HipChat, attempted to migrate away from Slack.

“We’d been loyalists to Slack for some time, but this winter we decided to break out of the box and try HipChat... that migration turned out to be a temporary one.”

Why did they return?

The analysis reveals that while HipChat offered similar features at a better price point, and arguably better project management integrations, it lacked the holistic narrative cohesion.

Slack had become the “poster child of collaboration.”

The friction of leaving Slack was not just technical (data migration) but cultural. Teams felt they were stepping back into the past. The narrative of “modernity” that Slack owned was so powerful that even a more logically priced, better-integrated competitor (for Jira users) felt inferior. This is the ultimate failure of the Utility Trap: even when you have better utility (integrations), you lose if your story is “old.”

Atlassian Stride Pivot: Too Little, Too Late

Recognizing the erosion of its shield, Atlassian attempted a narrative pivot with “Stride” in 2017. Stride was marketed as a complete reimagining of team communication, adding native voice and video to compete with Slack and emerging threats like Zoom. The marketing language shifted to “Team Chat That’s Actually Built For Business,” trying to imply that Slack was a toy while Stride was for serious work.

However, the narrative damage was irreversible.

The market had already accepted Slack’s definition of the category. Stride was viewed not as an innovator, but as a reactionary measure—a “me-too” product trying to patch the leaks in the HipChat vessel. The Narrative Shield had disintegrated.

Despite Atlassian’s immense resources and existing install base, they could not buy back the narrative dominance Slack had won organically. Users saw Stride as HipChat 2.0, carrying the baggage of the old brand, whereas Slack was seen as a new species of software.

The Capitulation: Narrative Surrender

The ultimate proof of narrative failure occurred in July 2018.

In an unprecedented move, Atlassian discontinued both HipChat and Stride, selling the intellectual property to Slack and advising its own customers to migrate to its competitor.

This event is a landmark case study in the power of narrative.

Atlassian did not lack engineering talent or capital. They lacked a compelling product story. They admitted that Slack’s narrative of “Where Work Happens”—and the ecosystem built around it—was superior to their own narrative of “Integrated Developer Tools.”

The “Utility Trap” had closed on HipChat.

By focusing on features (like video calling or screen sharing) rather than the human experience of collaboration, they lost the war for the user’s mindshare long before they lost the war for their wallet.

Atlassian’s decision to invest in Slack rather than fight them was a strategic admission that the “Narrative Shield” of the Atlassian ecosystem was no longer sufficient to protect an inferior user experience. They realized that a bad chat experience hurt the rest of their suite (Jira/Confluence). It was better to partner with the narrative winner than to let their own brand drag down the ecosystem.

Insights and Ripple Effects

The fall of HipChat suggests a broader trend in B2B SaaS: The consumerization of the enterprise. As decision-making power decentralized from the CIO to the end-user (Product-Led Growth), the “Shield” of being IT-approved (HipChat’s strength) weakened. Users chose tools that made them feel productive and connected (Slack).

Furthermore, the failure of HipChat demonstrates that integration is not a narrative. HipChat relied heavily on its integration with Jira as a moat. But integrations are technical features. Slack turned integrations into a story about automation and workflow reduction (”Make work life simpler”).

This subtle shift in framing—from “we connect to Jira” to “we automate your busywork”—allowed Slack to capture the value of the integration more effectively than the company that actually owned the integrated tool.

Case Study 2: InVision vs. Figma

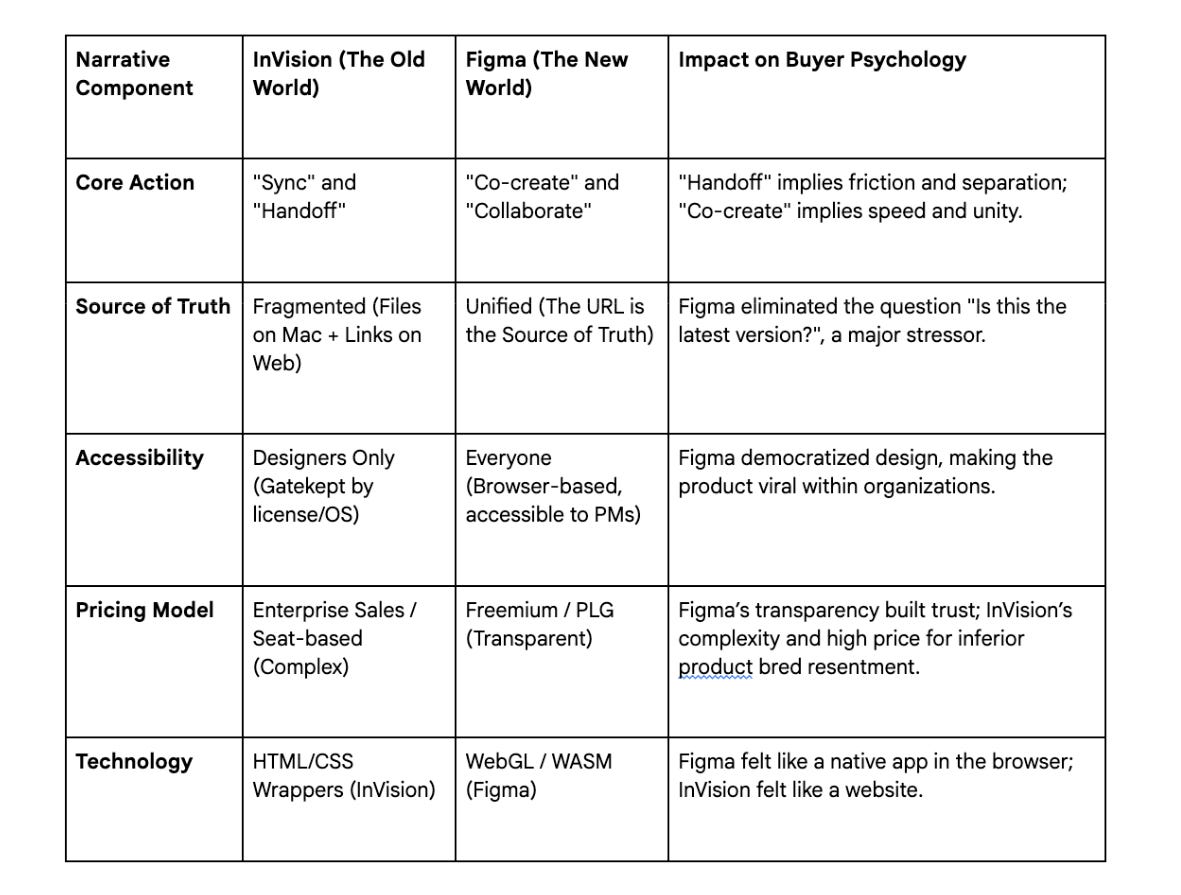

In the mid-2010s, InVision was the undisputed darling of the digital design world, valued at nearly $2 billion. Its Narrative Shield was constructed from the severe fragmentation of the design process at the time. Designers worked in desktop applications like Adobe Photoshop or Sketch, while developers and product managers lived in browsers. There was no bridge.

InVision’s narrative was “The Connected Workflow.”

They promised to bridge the gap between the designer’s static file and the developer’s code. They didn’t create the designs; they simply hosted them and made them “clickable.” This story resonated deeply because the pain point (handing off design specs) was acute. “Prototyping” became synonymous with InVision.

However, this narrative masked a fatal technical and philosophical flaw: InVision was a synchronization tool, not a creation tool. It relied entirely on the existence of other tools (Sketch) to function.

Its entire existence was a patch over a workflow inefficiency. If that inefficiency were ever solved at the source, InVision would cease to have a purpose.

The Vaporware Crisis: InVision Studio

Sensing the vulnerability of relying on Sketch (especially as Sketch remained Mac-only and Adobe was waking up), InVision attempted to seize the creation layer with the launch of InVision Studio. The marketing narrative for Studio was aggressive: it was pitched as the “most powerful screen design tool in the world,” promising advanced animation and responsiveness that would kill Sketch and Adobe XD.

This was a high-stakes narrative gambit.

InVision hyped Studio for months, releasing slick teaser videos that promised a level of fluidity and power never seen before. They built a massive waiting list. But when the product finally launched, the reality crashed against the narrative. Studio was plagued by bugs, performance issues, and a lack of feature parity with existing tools. It was sluggish and unreliable.

Here, the Narrative Shield turned into a Credibility Trap. By promising a revolution and delivering a beta-quality product, InVision shattered the trust of its user base.

The “Studio” narrative—that InVision could power the entire design process—was exposed as a fabrication. This failure is often cited as a classic example of “vaporware” marketing—selling the vision of a product that the engineering team could not deliver.

Users realized the story was better than the software.

Figma and the “Multiplayer” Narrative

While InVision was struggling to patch its synchronization narrative and fix the Studio disaster, Figma entered the market with a radically different story: “Design is a Team Sport.”

Figma didn’t just build a design tool in the browser; they built a multiplayer game engine for design. Their use of WebGL allowed for real-time collaboration, a technological leap that enabled a new narrative. InVision’s story was about handing off work (Designer → InVision → Developer).

Figma’s story was about working together (Designer + Developer + PM in the same file simultaneously).

This shift was profound. InVision’s “Connected Workflow” still implied separation—it connected two islands. Figma’s narrative of “Collaboration” implied a single continent.

Wonderbits explicitly notes:

“Figma arrived and changed everything... Everything was in the cloud... No need to download files.” This eliminated the “version control anxiety” that plagued InVision users, who were constantly managing “Final_Final_v3.sketch” files.

Table 2: The Shift from Synchronization to Real-Time Collaboration:

The Collapse: From $2 Billion to Zero

The speed of InVision’s collapse is a testament to the fragility of a shield built on workflow friction. As soon as Figma removed the friction entirely (by putting the design tool in the browser), InVision’s value proposition of “connecting” the workflow became obsolete. You don’t need a bridge if the river is gone.

The financial dissolution was absolute.

InVision, once valued at nearly $2 billion, announced in January 2024 that it was shutting down its design collaboration services entirely. It sold its remaining assets, like the Freehand whiteboard tool, to Miro. The company that once defined the category had been completely hollowed out.

This analysis confirms that InVision failed to “disrupt itself.” They clung to the “integration” narrative—trying to integrate with Sketch and Adobe—while Figma made integration irrelevant by becoming the platform. They failed to listen to customer feedback regarding basic feature improvements because they were too focused on the “Studio” moonshot.

They believed their own narrative—that they were the platform for everything—while neglecting the core “prototyping” utility that users actually paid for.

Third-Order Insights: The End of the File-Based Era

A deeper insight from the InVision/Figma war is the End of the File-Based Era.

InVision’s narrative assumed that “files” (Sketch files, Photoshop files) were the atomic unit of design. Figma’s narrative assumed that ideas and systems were the atomic unit, referenced by a URL.

By clinging to the “file” metaphor, InVision doomed itself to be a management layer for a dying format. This transition mirrors the shift from Microsoft Office (files sent via email) to Google Docs (links shared in chat). In SaaS, any company whose narrative relies on managing files rather than eliminating them is vulnerable to a “multiplayer” competitor. Figma’s success wasn’t just about design; it was about verifying the “browser-first” hypothesis for complex, high-performance software.

Case Study 3: Hopin’s Crisis Narrative Shield

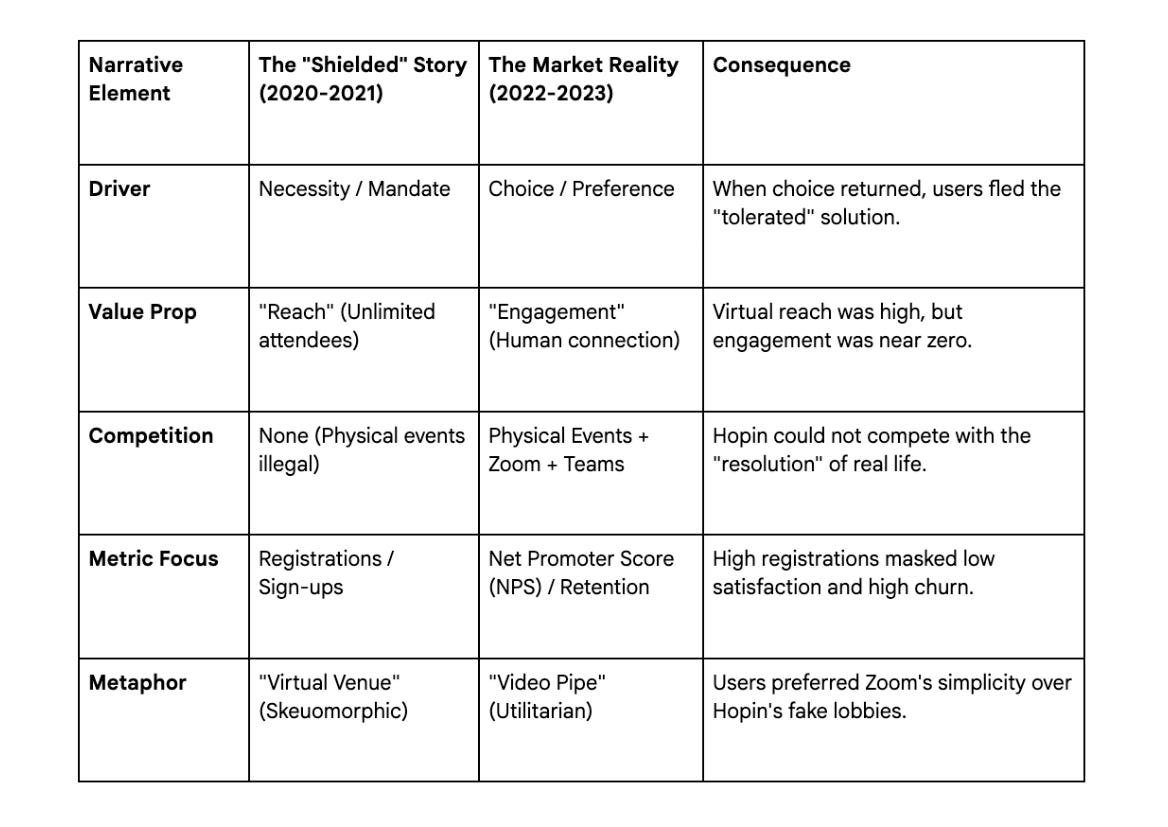

Hopin represents the most extreme example of a Narrative Shield in recent SaaS history. Founded shortly before the COVID-19 pandemic, Hopin’s platform for virtual events was perfectly positioned to catch the tidal wave of demand created by global lockdowns.

Their Narrative Shield here was the Lockdown Mandate.

Companies had to host events virtually; they had no choice. Hopin provided a “Virtual Venue” that mimicked physical spaces (Reception, Stage, Booths). This skeuomorphic narrative—”It’s just like a real conference, but online”—was incredibly comforting to panicked event organizers who were desperate to salvage their annual summits.

On the back of this demand, Hopin’s valuation skyrocketed. It went from a seed stage startup to a $7.75 billion valuation in roughly two years. This hyper-growth was interpreted by investors and the market as evidence of a revolutionary product. In reality, it was evidence of a monopoly on necessity. The “rising tide” of capital flooding into virtual events created a feedback loop where funding justified the narrative, and the narrative justified the funding.

False “Future of Events” Manifesto

Hopin’s narrative was grand: “The Future of Events is Hybrid/Virtual.”

They argued that the efficiency and reach of virtual events would permanently displace in-person gatherings even after the pandemic. They sold a vision of a world where geography was irrelevant.

However, this narrative ignored a fundamental human truth: Zoom Fatigue. While Hopin provided the utility of hosting an event, it struggled to replicate the serendipity and energy of physical interaction. As the pandemic dragged on, user sentiment turned against virtual events. They became chores, not experiences. Hopin’s product, which was technically essentially a wrapper around video streaming technologies, began to show its cracks. It was often buggy, difficult to configure, and expensive.

Competitors like Zoom, which offered a much simpler “Webinar” product, began to encroach. Dreamcast highlights a critical comparison: Hopin was suitable for “all kinds of events” but lacked a free plan and was complex, while Zoom was suitable for “meetings and webinars” and was simple. As the novelty of the “virtual lobby” wore off, users gravitated back to simplicity.

The Shield Dissolves: The Return to Physical

When the world reopened, Hopin’s Narrative Shield evaporated instantly.

The “Future of Events” turned out to be... actual events. Organizers rushed back to in-person gatherings. The “Hybrid” narrative—Hopin’s pivot attempt—failed to gain traction because hybrid events are exponentially more complex and expensive to produce than purely virtual or purely physical ones. A hybrid event requires two venues (one physical, one digital) and two production teams.

Hopin’s narrative that this was the “new normal” underestimated the budget and logistical constraints of their customers. They acquired multiple companies (StreamYard, etc.) to try and bolster its offering, but these disparate tools failed to cohere into a unified “Operating System for Events” in the way the narrative promised. The product story remained fragmented.

The “Virtual Venue” became a ghost town.

The Valuation Collapse

In a stunning reversal, Hopin sold its core events business to RingCentral in 2023. While the exact price was not disclosed, it is widely understood to be a fraction of its peak $7.75B valuation. The founder stepped down, and the “Hopin” brand as the titan of virtual events ceased to exist.

This collapse demonstrates that Market Conditions are not a Business Model.

A narrative that relies 100% on a temporary external factor (AI hype cycle, a pandemic) is a shield that will inevitably rust. Hopin failed to use the time and capital provided by the shield to build a product that users loved rather than one they tolerated. They bought growth, but they couldn’t buy retention.

Table 3: The COVID Bubble Narrative Deviation:

Hopin’s “Virtual Venue” Trap

Hopin’s specific narrative mistake was the “Virtual Venue” metaphor. By trying to recreate the physical layout of a conference (lobbies, expo halls) on a screen, they created a skeuomorphic interface that felt clunky and artificial. It was “Second Life” for corporate webinars.

Competitors like Zoom did not try to be a “venue”; they just tried to be a “video pipe.” Zoom’s simplicity won out over Hopin’s complexity for the vast majority of use cases. People didn’t want to navigate a fake 2D lobby; they just wanted to click a link and see the speaker.

Hopin’s narrative of “immersion” actually created friction.

The lesson here is that digital products should leverage digital advantages (speed, searchability, recording), not mimic physical limitations (walking between rooms).

Case Study 4: BlueJeans vs. Zoom

BlueJeans positioned itself as the “professional” choice for video conferencing. Its narrative was built around Interoperability (connecting Cisco hardware to Skype to browsers) and Security.

The Narrative Shield for BlueJeans was the IT Department.

BlueJeans sold to CIOs, not users. Their story was: “We are secure, we’re encrypted, and we work with your expensive boardroom hardware.” This shield protected them for years because IT directors held the keys to software procurement. Snippet highlights that giants like Facebook and Disney chose BlueJeans over Zoom initially for these reasons.

Zoom’s Viral Simplicity

Zoom, led by Eric Yuan, bypassed the IT department and went straight to the user with a narrative of “It Just Works.”

While BlueJeans was talking about “AES-256bit encryption” and “Dolby Voice,” Zoom was focusing on the friction of joining. Zoom’s “one-click join” was a narrative device as much as a feature. It told the user: “We respect your time.” The “Freemium” model allowed anyone to start a meeting, creating a bottom-up adoption curve that overwhelmed IT departments.

The “Video Quality” Myth

BlueJeans often touted superior audio/video quality (Dolby partnership) as a differentiator. However, the market proved that Reliability > Quality. A 4K video stream that takes 5 minutes to set up is infinitely less valuable than a 720p stream that connects instantly.

Zoom’s narrative focused on video quality stability over fidelity. They optimized for packet loss, ensuring the call didn’t drop even on bad Wi-Fi. BlueJeans, with its heavy enterprise architecture, often struggled on the open internet compared to Zoom’s nimble architecture. G2 shows user reviews complaining about BlueJeans camera defaults and audio issues with Bluetooth, friction points that Zoom relentlessly polished away.

The Sunset

In 2020, Verizon acquired BlueJeans for roughly $500 million—a modest exit compared to Zoom’s peak market cap of over $100 billion. However, in a final blow to the “Enterprise” narrative, Verizon announced in 2023/2024 that it was sunsetting the BlueJeans product entirely.

The failure here was a Go-To-Market Narrative Failure.

BlueJeans believed the narrative that “Enterprise” meant “Complex and Secure.” Zoom proved that “Enterprise” actually meant “Simple enough that employees will actually use it” (Consumerization of IT).

The Narrative Shield of “Security” was pierced by the arrow of “Usability.” When the pandemic hit, employees simply started using Zoom because it was easier, forcing IT departments to catch up. BlueJeans, hiding behind the IT fortress, was left in an empty castle.

The Calculus of Narrative Erosion

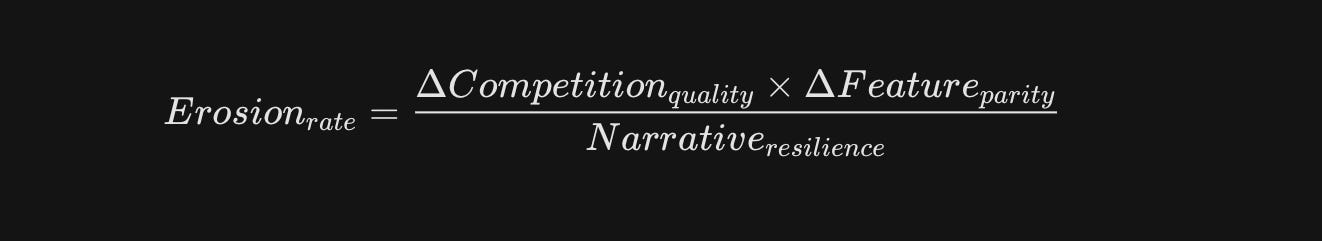

The erosion of a Narrative Shield isn’t random. It can be modeled mathematically as a function of competitive density and narrative differentiation:

Where Narrative Resilience is determined by the depth of the emotional connection and the clarity of the strategic vision.

As competitive quality rises (e.g., Zoom entering the video market), if Narrative Resilience is low (as with BlueJeans), the erosion rate of market share accelerates exponentially, regardless of feature parity.

Diagnostic Indicators of a Narrative Shield

So, how do you know if you are growing because of Narrative-Market Fit (NMF) or just a Narrative Shield? Based on my forensic analysis of these four companies, we can identify clear diagnostic indicators that a startup is operating under a Narrative Shield rather than true Narrative-Market Fit:

Metric Dissonance: Revenue is growing, but Net Promoter Score (NPS) or Daily Active User (DAU) / Monthly Active User (MAU) ratios are declining (Hopin).

The “Integrator” Identity: The company defines itself by what it connects to, rather than what it is (HipChat connecting to Jira, InVision connecting to Sketch).

Skeuomorphic Metaphors: The product narrative relies on copying the physical world (Hopin’s “Venues,”) rather than reimagining digitally native workflows (Slack’s “Channels,” Notion’s “Blocks”).

The Gatekeeper Reliance: Sales rely heavily on a specific gatekeeper (IT Director) while end-users actively dislike the tool (BlueJeans).

The Vaporware Pivot: The company announces a massive, revolutionary new platform (InVision Studio) to distract from the stagnation of the core product.

The Fix: Paying Down “Story Debt”

Just as companies accumulate Technical Debt (bad code written for speed), they also accumulate Story Debt.

HipChat had Story Debt: They never updated their “Utility” story to an “Empathy” story.

InVision had Story Debt: They never updated their “Handing Off” story to a “Multiplayer” story.

When Story Debt becomes too high, the Narrative Shield collapses.

The winners in these case studies (Figma, Notion, Slack, Zoom) all built Community-Led Narratives.

Figma users shared files.

Slack users shared bots/integrations.

The losers (InVision, HipChat, BlueJeans) built Vendor-Led Narratives.

They spoke at the customer, not through the customer. A community narrative is self-healing; a vendor narrative is fragile.

Don’t Mistake a Tailwind for an Engine

For future SaaS startups, the lesson is clear: Do not mistake a tailwind for an engine.

A tailwind (Narrative Shield) will eventually stop blowing.

Only a powerful, resonant, and adaptable product story (Narrative Engine) can propel a company against the headwinds of competition and market saturation.

The most dangerous moment for a company is not when it is struggling, but when it is growing for the wrong reasons.

If you suspect you are shielding, you need to lower the shield and fix the foundation. You need to transition from Utility to Culture, from Handoff to Collaboration, from Necessity to Preference.

Naming the shield is the first step to lowering it and building true resilience.

Want to check your own Narrative Resilience?

VEC Studio helps B2B SaaS founders and PMMs pay down their Story Debt before the market calls it in. We specialize in transforming fragile Vendor-Led narratives into resilient Product-Led Storytelling engines. If you’re ready to stop shielding and start scaling, let’s talk.