Substack’s Narrative Dilution: When Venture Growth Dilutes the Gospel

How Substack’s Venture-Scale Ambition Is Eroding a Narrative Writers Were Ready to Stake Their Lives On

I didn’t start this investigation because I wanted to write about Substack.

I started because one paragraph stopped me cold.

On 27th January 2025, David I. Adeleke, the Founder of Communiqué, published an essay titled “Substack lost its way.” It was a thoughtful reflection on why the platform feels different now: noisier, more chaotic, less focused. Buried inside his essay was a line that wasn’t outrage. It wasn’t an accusation.

It was a signal flare.

“Of the 11 fellows in my [Substack Grow Fellowship] cohort, three have moved off Substack, and one no longer publishes. My mentor during the fellowship, Casey Newton, has also left the platform and moved his publication Platformer to Ghost. Perhaps this should have been the strongest signal for me, given that Casey was one of Substack’s earliest champions and support beneficiaries. For him to have left the platform so strongly and publicly as he did, I should have sensed what was coming.”

That paragraph sent me down a rabbit hole.

It forced me to look past the usual headlines about content moderation and “Nazi bars” and look at something much more fundamental to us as SaaS founders and Product Marketers: The Product Narrative.

Specifically, it led me to investigate the writers who—even after benefitting from Substack’s ecosystem—left the platform. I’m not talking about those who left solely for political reasons. I’m talking about the “Breadwinners.” The operators. People like Nathan Baschez & Dan Shipper (of Every.to) Kyle Poyar, Jacob Donnelly, Isabelle Roughol, and thousands of others.

Why did they leave?

My investigation revealed a pattern that every venture-backed founder needs to see. It suggests that as Substack chased the growth required to justify its venture-scale valuation, it didn’t just add features; it diluted the very narrative that its best customers had staked their livelihoods on.

Today, we aren’t just looking at churn.

We’re looking at Narrative Dilution.

We are looking at what happens when a company’s financial ambition rewrites its product story, leaving its most successful users with no choice but to walk out the door.

My Hypothesis: The Cost of Unexamined Scale

Let me be explicit upfront.

This is not a story about content moderation. It is not about free speech.

And it’s definitely not about who Substack should or should not host.

I deliberately excluded anyone whose primary reason for leaving Substack (i.e., the likes of Casey Newton) was content governance or political disagreement. Not because those debates don’t matter, but because they obscure a deeper, more instructive failure.

This is about product narrative dilution.

Substack is not unique here.

It is simply the clearest specimen we have.

My hypothesis for this deep dive is simple but uncomfortable.

As a startup takes on more capital and hits new jaw-dropping valuations, its quest for new growth vectors inevitably inflicts dilution on its originally compelling product narrative.

I have thoroughly examined and written before about the Narrative Shield—the story that protects a startup from criticism while it builds. Substack had one of the strongest shields in tech history. It promised an “Empire of One.” It promised an escape from the algorithm. It promised that the relationship between writer and reader was sacred and direct.

But shields degrade when they are not reinforced by product decisions.

What I found in my research is that Substack’s “Big S” story—the overarching narrative of independence—has been slowly cannibalized by its “Venture Story”—the need to become a centralized social network to justify a $1 billion+ valuation.

And the people leaving? They aren’t leaving because they failed. They’re leaving because they succeeded—and found that Substack’s diluted narrative no longer had room for their success.

Let’s look at the evidence.

Kyle Poyar’s Irony (Or, How Incentives Change Belief)

If you want to understand Narrative Dilution, you have to look at Kyle Poyar.

Kyle is the author of Growth Unhinged, a massive newsletter for SaaS growth leaders, which I’ve subscribed to since day one. For a long time, he was one of Substack’s golden boys. He was the proof that you could build a serious B2B audience on the platform.

In December 2024, Tyler Denk, the CEO of beehiiv (Substack’s loud, infrastructure-focused competitor), published a piece called “Death by a thousand substacks.“ In it, Tyler argued that Substack was stripping writers off the personalized experience they were promised, prioritizing the “Substack Network” over the individual writer’s brand.

He explicitly called out Kyle’s newsletter as an example of Substack’s “dark patterns.”

Kyle’s response at the time was swift and defensive.

He wrote:

“Today the founder of beehiiv wrote a pointed Substack takedown post... My newsletter was explicitly called out as an example of Substack’s ‘50 shades of dark patterns’. My two cents: ignore it. What beehiiv misses is that Substack fosters a community of writers and a community of readers who want to engage with their ideas... We won’t thrive by tearing each other down. With a platform like Substack, we all grow together.”

That was December 2024. Kyle was using the Narrative Shield that wasn’t yet leaking for him. He was defending the “Community” story because it was still working for him. At that point, his newsletter was 100% free. He benefited from the network effects. The story aligned with his incentives.

Fast forward less than two years.

Kyle Poyar is no longer on Substack.

In a move that drips with narrative irony, he switched to—you won’t believe it—beehiiv. The very platform he told his readers to ignore.

Why? What changed?

Did Kyle change his morals? No.

The product narrative diluted to the point where it conflicted with his business reality.

When Kyle decided to turn on paid subscriptions and treat his newsletter as a serious business, Substack’s “Community” narrative suddenly looked like a “Platform Trap.”

Here is what Kyle wrote upon leaving:

“I got tired of complaining about the limitations of Substack now that I’m more serious and finally did something about it. I switched over to beehiiv on December 31st and honestly I wish I had done it sooner... It felt like Substack stopped innovating for writers and decided to become a closed social media platform instead.”

Read that last sentence again.

“Decided to become a closed social media platform instead.”

That is the sound of a Narrative Gap snapping open. Kyle needed infrastructure (APIs, analytics, segmentation). Substack offered him a social feed (Notes, Chat).

He continues, and this is the smoking gun for B2B founders:

“Now that I’m on beehiiv I’m taking more control of the newsletter look and feel, improving deliverability, collecting better data about readers, learning what an API key is, setting up automations, and no longer paying a 10% Substack tax.”

“Learning what an API key is.”

In 2024, Kyle defended Substack because the narrative of “Community” shielded him from the lack of features. But as he scaled, the lack of an API wasn’t a “philosophical choice” by Substack anymore; it was a business hostility. It was a lock-in mechanism designed to keep his data trapped in their walled garden to support their valuation, not his business.

Kyle didn’t leave because he was angry. He left because he outgrew the story.

The Structural Ceiling (Every.to, Jacob Donnelly, and Michael Nadeau)

Kyle isn’t an anomaly. He is part of a pattern of “Breadwinners” realizing that Substack is optimized for the “Yeast”—the masses of new writers—rather than the businesses that drive the industry forward.

Let’s look at Every.to.

Nathan Baschez and Dan Shipper were early darlings of the paid newsletter boom. Nathan was actually the first employee at Substack. If anyone believed in the mission, it was him.

But they left years ago. Why?

I commented on David’s post that this gave me perspective on why Every.to left:

“There will be a return... to something looser and more adaptive: individual writers growing into small media companies, collectives, or tightly curated networks... We are already seeing this.”

Every.to wanted to bundle niche newsletters into a single subscription ($200/yr). They wanted to create a “Netflix for Business Writing.”

Substack’s product narrative is built on the atomized writer. It connects readers to one writer. It breaks when you try to build a Collective.

Nathan and Dan realized that to build a media company, they needed control over the backend. They needed to bundle. They needed custom permissions. Substack’s refusal to build these features wasn’t a roadmap oversight; it was a narrative choice. Substack needs the relationship to be with Substack, not a third-party bundle.

So, Every.to built their own CMS.

They churned because the platform’s ambition (to be the destination) competed with their ambition (to be the destination).

Then there is Jacob Donnelly.

Jacob runs A Media Operator, a premier B2B publication.

He didn’t rage-quit. He reasoned his way out:

“When I first started A Media Operator, it was the easiest way to start writing... I don’t think A Media Operator would be where it is today if it had not been for that.”

This is important. Most of these founders acknowledge Substack’s value in the zero-to-one phase. The narrative works when you are small.

But then comes the inflection point:

“I realized something incredibly important… I needed to have complete control of my email list. ... I obviously wouldn’t want to email everyone; not even everyone on my premium membership. It might not be right for them. I would need the ability to create a segment and Substack doesn’t allow that. It’s built for newsletter/blogs, not marketing operations.”

“It’s built for newsletter/blogs, not marketing operations.”

This is the dilution. Substack pitches itself as a place to “build an empire,” but their product decisions (no segmentation, no API, no pixel tracking) force you to remain a hobbyist.

Jacob realized that to run a B2B business, he needed to track leads, segment users, and optimize SEO. Substack’s venture-backed need for “network effects” meant they prioritized features like “Notes” (which keeps users on Substack) over “Segmentation” (which helps Jacob sell to users).

Michael Nadeau’s Quiet Exit

This pattern repeats with Michael Nadeau of The DeFi Report. His exit wasn’t loud, but it was structurally damning. He moved to beehiiv because his business had “outgrown” Substack’s starter tools.

Specifically, he needed API access to integrate his content into a broader business ecosystem. He needed to consolidate his research, market insights, and on-chain data services onto a single owned and operated platform.

Substack offers an “export” button, but they do not offer an API. Why? Because an API allows you to plug Substack into other tools (like a CRM or a data dashboard), reducing your dependence on their interface. By denying an API, Substack attempts to force dependency. But for operators like Nadeau, dependency is a risk factor.

He left not because the writing tool was bad, but because the “Empire of One” narrative was a lie if that empire couldn’t connect to the rest of the world.

The Arithmetic of Departure (Mill Media and Amy Odell)

Narratives can survive friction. They rarely survive arithmetic.

When a startup takes on massive capital, it must capture value. Substack does this via a 10% flat tax on revenue. In the early days, 10% feels like a fair partnership. “We win when you win.”

But as a business scales, that 10% stops feeling like a partnership and starts feeling like an anchor.

The Mill Media Calculus

Mill Media is a UK-based local news network. They didn’t leave out of malice.

They did the math (as did Kyle Poyar eventually):

“That would represent more than £100,000 pounds for us next year.”

They anticipated £1 million in turnover. Paying Substack £100,000 for what is essentially email hosting and a payment gateway is indefensible P&L management.

By moving to Ghost, they pay a flat SaaS fee.

Ghost charges based on audience size—for a company reaching 10,000 members, the cost is around $199/year (plus extras for team seats), compared to the uncapped 10% revenue share. The difference allows them to cut platform costs to less than a fifth of what they were paying on Substack.

That savings isn’t just profit. It is the cost of hiring another investigative journalist.

Amy Odell and the Burnout Tax

Amy Odell, who writes the fashion newsletter Back Row, moved her 66,000+ subscribers to beehiiv in early 2026. Her reasoning connects the financial “tax” directly to the human cost of production:

“Substack also takes a ten percent cut of writer earnings… for me — thanks to the generous support of paid subscribers — that was really starting to add up... Thanks to ad revenue and the savings I’m making by moving off Substack, I’m able to hire some freelance help… which goes a long way toward helping me not burn out.”

This is where the “Venture Narrative” kills the “Product Narrative.”

Substack cannot cap its fees because its valuation depends on capturing the upside of its “Whales.” But the “Whales” are smart businesses. They know that software costs should scale down (marginally) as volume goes up, not scale linearly forever.

For Amy, the 10% fee wasn’t just money lost; it was help she couldn’t hire. It was burnout she couldn’t alleviate. By moving to beehiiv, she aligned her tech stack with her mental health.

In her words:

“This newsletter is my livelihood... In all honesty, I have been agonizing over it for months.”

She didn’t want to leave. The product narrative pushed her out.

Substack’s Narrative Inversion (Isabelle Roughol and Lyz Lenz)

Perhaps the most damaging form of dilution happens when the platform begins to compete with the creator for the reader’s attention. This is Narrative Inversion.

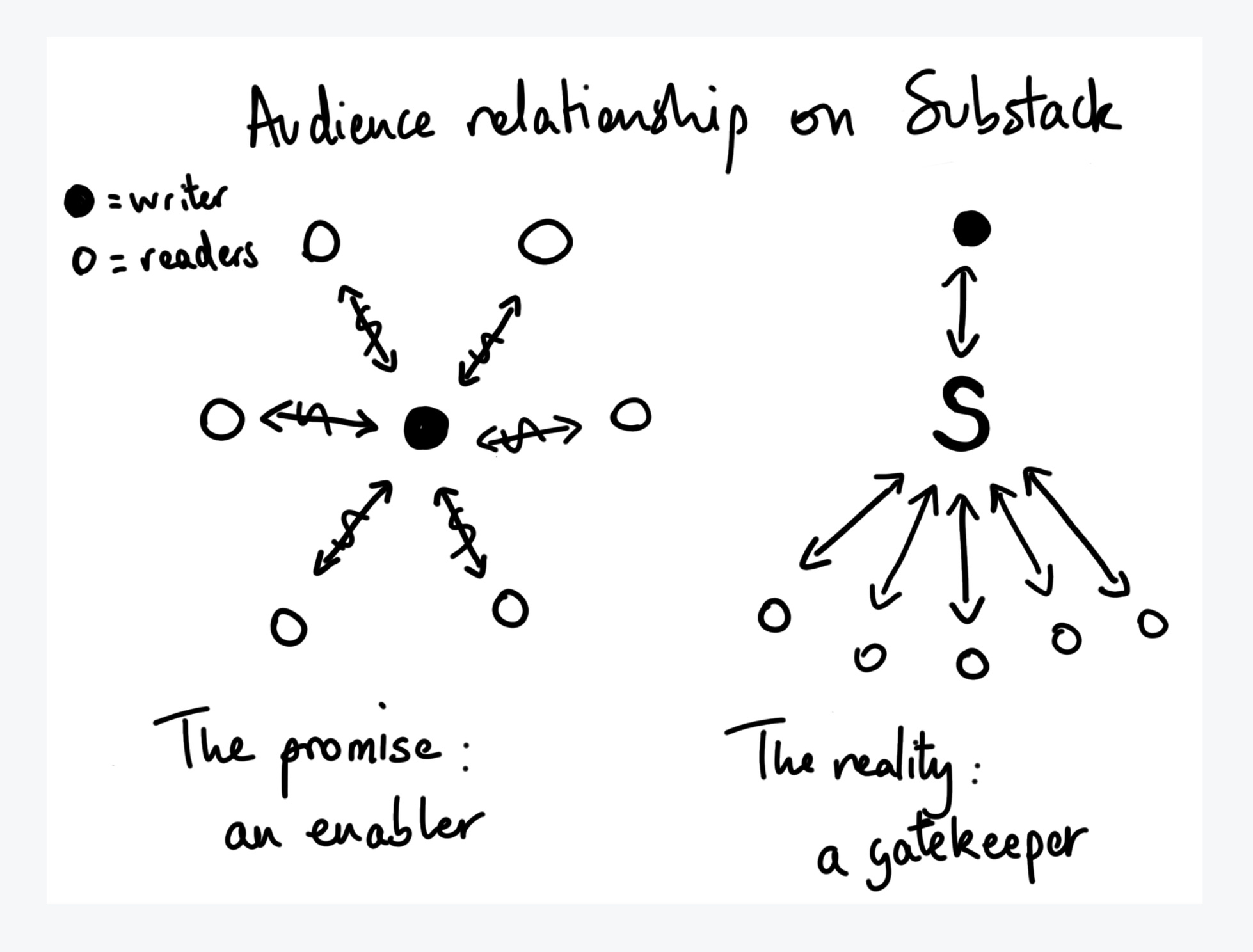

The original Substack promise was: “You own the relationship.”

The diluted Substack reality is: “We own the user; you provide the content.”

Isabelle Roughol’s Clarity

Isabelle Roughol, the former LinkedIn editor who runs Borderline, articulated this shift with devastating precision when she moved to Ghost:

“I wanted newsletter software that ‘could recede in the background and allow my own brand to shine.’ I could see the signs of Substack becoming something quite different... My readers were becoming Substack’s users, and I was becoming a provider of content to the company I had hired to be my provider of software.”

This captures the essence of the dilution. Substack began as a tool (software you hire). It drifted toward becoming a destination (a platform that hires you).

When Substack pushes “Notes” (its Twitter clone) or its app, it is prioritizing its retention over Isabelle’s brand connection.

“All writers became lumped together in a collective they had never asked to be a part of... with assorted unsavoury characters Substack refused to distance itself – or the rest of us – from.”

Perhaps, throughout my research, no one captured this better than Isabella Roughol in their reasons for leaving. In her essay, “We’ve Been Thinking of Substack All Wrong,” she nailed it with this sketch:

Lyz Lenz and the “Enshittification”

Lyz Lenz, author of Men Yell at Me, moved to Patreon in late 2025. Her departure highlights how the “Social Pivot” actively degraded her relationship with readers:

“Substack has transitioned to more of a social media site... I have also heard from so many of you that you aren’t getting your emails because Substack has shifted to pushing users to use the app.”

This is a critical technical betrayal.

Substack started suppressing email delivery (or de-prioritizing it) in favor of app notifications because app usage drives their valuation metrics (DAU/MAU), whereas email opens only drive Lyz’s business.

No wonder Lyz said:

“I don’t want to serve as a one-person IT department for my readers and listeners who can’t resolve their account problems because Substack’s ‘support’ has been reduced to a bot.” (Quoting Anne Helen Petersen, echoed by Lyz).

When a platform “enshittifies”—a term coined by Cory Doctorow and cited by Anne Helen Petersen in her exit post —it shifts value from users to shareholders. Substack’s refusal to moderate hate speech was the headline, but the product decision to force readers into an app experience they didn’t ask for was the structural failure that drove Lyz away.

The Scale Issue (Adam Beach and MyGolfSpy)

Finally, we have to talk about scale.

Product narratives often have a “size cap.”

As I detailed in a previous deep dive, ‘The 3 Evolutionary Levels of SaaS Product Storytelling,’ a story that resonates with a freelancer might repel an enterprise.

Adam Beach runs MyGolfSpy, a massive publication with over 200,000 subscribers. He migrated to beehiiv not for politics, but for physics:

“Growth and Scalability: After migrating, MyGolfSpy successfully scaled to over 200,000 subscribers by leveraging advanced growth tools.”

At 200,000 subscribers, you are not writing a “letter.” You are running a media operation. You need referral programs that actually track conversions. You need robust segmentation to sell different products to different golfers (e.g., “High Handicappers” vs. “Scratch Players”).

Substack’s product narrative treats all 200,000 subscribers as a single blob of “readers.” Adam Beach needed a “Tech Stack”.

By moving to beehiiv, he gained “better list segmentation and referral programs”. He also gained “Data Ownership”—not just the ability to export a CSV, but the ability to use that data to drive business decisions.

This proves that Substack’s “Empire of One” narrative fails when the “One” becomes a “Many.” They built a tool for authors, but marketed it to businesses and failed to evolve the product to match their original promise to businesses). So when the authors became businesses, the product couldn’t hold them.

My (New) Narrative Dilution Framework

So, what are we seeing here?

When I look at Substack and those leaving, it’s not just that they’re marching towards becoming a social platform. It is that the product has failed to evolve to truly serve the in-depth writer-reader relationship it once promised.

Here is the pattern of Narrative Dilution that I want you to look for in your own company (and the tools you use):

The “FounderSignal” Phase: The startup launches with a pure story. “We are for X.” (Substack: We are for writers owning their audience). This attracts the true believers.

The Venture Velocity Phase: The startup raises big money ($65M+ for Substack). The valuation demands viral growth. The product roadmap shifts from “Deepening Value” (APIs, tools for power users) to “Expanding Surface Area” (Social feeds, apps, discovery algorithms).

The Incentive Drift: The features that drive the platform’s valuation (Time in App) begin to conflict with the user’s goals (Owning the relationship). Substack launches “Notes” to compete with Twitter, distracting from the core email value.

The “Breadwinner” Exodus: The most successful users—those who actually built businesses—realize the platform is now optimized for the “Yeast” (beginners who need the algorithm) rather than the “Breadwinners” (who bring their own distribution).

The Narrative Collapse: The “Breadwinners” leave. They take their audiences with them. The platform is left with a diluted story and a churn-heavy user base.

Tyler Denk called this out perfectly:

“If you’re not a breadwinner, you’re the yeast.”

Substack’s venture quest forced it to optimize for the yeast. And in doing so, they diluted the narrative that attracted the breadwinners in the first place. It’d take a lot to win them back. A whole lot.

You Can’t Eat Valuation

This is the lesson for us.

Substack is not a “bad” product.

It is a product suffering from Story-Market Divergence.

Its original story (”Empire of One”) attracted people who wanted independence. But the business model it is drifting towards (Venture Scale) is forcing it to build a dependency engine (The Network).

Kyle Poyar didn’t want a network. He wanted an API key.

Jacob Donnelly didn’t want discovery. He wanted segmentation.

Mill Media didn’t want a partner taking 10%. They wanted a vendor taking a flat fee.

Isabelle Roughol didn’t want to be a content provider. She wanted to be a brand.

Lyz Lenz didn’t want an app that hid her emails. She wanted a direct line to her readers.

As I write this, I am still here. David I. Adeleke is still here. We are both running 100% free newsletters, chasing the growth and exposure that Substack’s “Network” promises. At roughly 370 subscribers, I want that reach. My goal for 2026 is hitting 5,000 subscribers. David, if I’m not mistaken, needs that reach to negotiate better banner ads and brand collaboration contracts. For now, the freemium model favors us. It allows us to sell ad inventory or gain industry recognition based on reach.

But I know what is coming.

Once we hit the ceilings that Kyle, Jacob, and the others hit, Substack’s narrative will no longer resonate. The Narrative Shield will break for us, just as it broke for them. We will be forced to seek the very infrastructure—APIs, segmentation, granular control—that they left to find.

And the tragedy is that Substack could build these things. It is baffling that a platform valued at over half a billion dollars still lacks basic editor functions. You cannot insert a Table of Contents with a click. You cannot add simple data tables. You cannot easily embed GIFs in certain contexts.

Substack has the right to chase venture-scale growth.

But neglecting to evolve the product to match the narrative that turned their earliest, best customers into natural advocates is not just strategic negligence. It is blindly digging their own grave.

As a startup scales, you must tender to improving the product to match your once-compelling narrative before doing everything possible to acquire more users. If you invite people to stake their lives on your platform, you owe them an infrastructure that grows with them.

If your venture ambitions force you to cap their ceiling, they will leave. And as we saw with Kyle Poyar, the very people cheering you on today will be the ones writing the migration tutorials tomorrow.

So, here is my question for you:

Look at your product roadmap today. Are the features you are shipping reinforcing the story you sold to your best customers? Or are they serving a new story—one required by your investors—that slowly dilutes the reason people bought you in the first place?

Don’t let your valuation become the villain of your product story.

What to do next:

If you are a B2B founder or PMM and you feel your product narrative might be drifting away from the reality of your power users, let’s talk. I help companies audit their Product Story Gap (I literally have a book in the works and you can read the first chapter here) before it turns into churn. Learn more at VEC Studio or book a session, and let’s ensure your narrative scales as fast as your ambition.

This is a really brilliant writeup. So a product can have a broken narrative shield, but for some users (like you and David for now) it's not at the point where you have to make a choice to pivot. What if it makes sense to hold that tension? At some point too for the product, you have to decide if your audience has changed (Breadwinner/Yeast).

This is really good. Damn!